Tibor Hajas: Tumo I, 1979

John P. Jacob:

THE ENIGMA OF MEANING:

TRANSFORMING REALITY IN HUNGARIAN PHOTOGRAPHY

All the manifold tendencies in art have

as their ultimate aims to represent our new life true to reality-discarding

superficial brilliance-in works inspired by great ideas and of high moral

standard. In this, the State too, plays no small part. Not only by frequently

bestowing orders of great importance on our artists and thereby encouraging

emulation between them but also by constantly helping them to at-tain an

awareness of the essence of socialism. The imagination of ar-tists inspired

by their tasks is thus disciplined and ennobled so that it can bear fruits

of value. (1)

Faith in the evidential value of the photograph is

the foun-dation upon which the many forms of photographic practice have

been built. Not until the advent of electronic manipula-tion of photographic

imagery in popular culture of the 1970s, in fact, had the American public

seriously considered the reliability of photographic representation. In

the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, however, the evidential value of the

photographic image is a construction which many contem-porary artists flatly

reject. If we are to comprehend their work, we must begin by foregoing

our faith in the photo-graph. We must acknowledge with them the thin skin

of ideology that holds our perception of reality, of our culture and our

history, together.

In the Soviet Union, photography has often been

used to depict the potential dis-integration or separation of reality from

its photographic representation. This potential was ex-plored in the Revolutionary

era by artists such as Alexandr Rodchenko. Rodchenko ascribed ideological

significance to the angle of the camera, believing it to possess powerful

nar-rative and symbolic associations with bourgeois tradition. He identified

the ideological function of art and, by harnessing it, sought to define

revolutionary perspective. “The revolu-tion does not consist in photographing

workers' leaders in-stead of generals while using the same photographic

techni-ques as under the old regime, or under the influence of Western

art,” he wrote. “A worker photographed like Christ, a woman worker photographed

like the Virgin Mary, is no revolution... We must find a new aesthetic...to

represent the facts of socialism in terms of photography.” (2)

By 1930, in the leading article of the first issue

of “USSR in Construction,” ideologues were demanding that “photography

must serve the country not in a haphazard, un-systematic way, but constantly

and according to a plan.” (3) Thereafter, Soviet photographers joined increasingly

with the press. “[Soviet] photography passed through years of seek-ing

and struggling, of chaos, misunderstanding and mistakes before finally

maturing as the powerful medium of photo-journalism, which continues to

perform the functions defined for it from the outset: to inform, disseminate

and educate.” (4)

In the 1930s many of the practitioners of the experimental

New Vision found themselves and their work subject to increasing critical

scrutiny. As the experimental period came to a close in the Soviet Union,

the photograph, like all other forms of visual expression, came under State

control. Like many other artists, Rodchenko was condemned for his “formalism.”

In 1931 Rodchenko was charged with “attempting to put proletarian art on

the path of Western advertisement art, formalism and aesthetic.” (5) In

the end, anti-formalist critics crushed artistic experimentation by declaring

its failure to satisfy the ideological requirements of revolutionary society.

Thereafter, cultural uniformity under the control of the State was ruthlessly

enforced.

In 1934 at the First All Union Congress of Soviet

Writers, Socialist Realism was ratified as “the only artistic style acceptable

to a Socialist society.” (6) This declaration rendered all forms of artistic

experimentation, formalist tendencies, or Western influence in any field

of creative expression essentially anti-Socialist and therefore illegal.

Following the ratification of Socialist Realism, photo-journalism became

(and to-day remains) the dominant trend in Soviet and Eastern European

photography.

Despite imposed limitations, it has fallen to the

artists of these nations to speak as the “voice-of-the-people.” Traditionally,

this position has been held by poets, whose gift could be discreetly transported

and freely shared. Following the thaw of the late 1950s in the Khrushchev

era, restrictions on visual artists were significantly relaxed. Communication

between East and West improved, and international travel became a possibility.

During this period especially, visual ar-tists began to break with the

doctrine of Socialist Realism and to adopt critical positions in their

work. This break from Realism was seen by many as an attempt to return

to realism. Such a return could be effected only by the complete dismantl-ing

of Socialist Realist aesthetics and of the structures that support them.

A dismantling of this magnitude, however (necessarily taking into account

all forms of ideological production, including the printed and electronic

media), remains impossible.

Today the aesthetic of Socialist Realism is rejected

for its failure to acknowledge the rich cultural traditions shared by the

nations of Central Europe. In dismissing the enforced Soviet aesthetic,

artists are rejecting “Eastern Europeanness” in favor of a pre-Warsaw Pact,

nationalist self-identification (nationalism is itself a primary taboo,

indicating in a work of art its maker's relation to Sovietization).

In the present political and cultural situation, Hungary is considered

the most stable and consistently liberal of the Soviet bloc nations. Political

progress has been made slowly in Hungary since the Revolution of 1956.

To achieve the goal of socialist democracy, the Hungarian Socialist Workers'

Party (HSWP) has gradually recognized a plurality of voices within the

fields of culture and politics, providing the working classes (including

cultural workers) with a role in the exercise of power. By listening to

dissenting voices, and by incorporating their ideas into the party program,

the HSWP has proposed to regain legitimate authority in the eyes of the

working people. As János Kádár declared in 1980, “our most important method

is persuasion, and not ordering people about.” (7)

Today, artists in Hungary are considered full members

of the socialist State and participate in the construction of socialist

democracy. The artist need not be a member of the party, only a responsible

citizen whose work performs a relevant task, as determined by the various

ministries, within the socialist structure. The Hungarian artist is offered

a role in the exercise of power by creating work that will help the State

to grow; the artist becomes a “cultural director” in a system of directed

culture. In compensation, he or she is rewarded with the resources to continue

such work.

It has been said that the arts in Hungary have “opened up,” that they

have transcended the boundaries imposed by Socialist Realism. Yet, until

very recently, the arts have opened to diversity largely to the extent

that they show their appreciation of socialism. “The characteristic features

of the past thirty years are a readiness to accept things, the presumption

of good intentions and understanding,” declared István Katona, a former

leading member of the Central Committee of the HSWP, “as long as no one

takes action against the socialist system and its political foundations.”

(8) According to György Aczél, a member of the Hungarian Politburo and

head of the Institute of Social Sciences of the HSWP, “there is no opposition

that has to be reckoned with in Hungary... there is no censorship in our

country.” (9) The HSWP has traditionally regarded oppositional criticism

as coming from “maladjusted, untalented, mentally troubled and/or disappointed

people who never blame themselves but always society,'' (10) and whose

opinions are not worthy of attention. If what they have to say has any

connection with reality, it is strictly by chance.

Hungarian audiences have long been protected from

any influence that might be considered harmful through State control of

all cultural institutions. Despite the relaxing of restrictions in recent

years, experimental artists are still regarded with suspicion in Hungary

and throughout Eastern Europe. Until approved by party cultural officials,

experimental work is regarded as having more in common with Western than

with home interests. Vanguard Hungarian artists are rarely prevented from

working; they support themselves with nonartistic jobs, the materials they

require are generally available, and they are free to pursue their artistic

interests in their homes. Nevertheless, few exhibition or publication opportunities

exist for them in their own nation. They cannot complain that their work

is censored, only that it is not seen. The artist who chooses to work outside

the system of State direction is thus denied the possibility of performing

a social function.

Until very recently, all experimental artists in

Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union constituted a parallel culture, an

unofficial culture that never intersected with official, or Statesanctioned,

culture. (11) In the past, developments in parallel culture within these

nations have tended to occur in relative isolation; artists in Poland,

for instance, often knew as little as Western Europeans and Americans did

about artists working in Hungary. Whereas Western perception has tended

to regard Eastern Europe as unified and monolithic, in fact, these nations

are profoundly divided.

Even in the most difficult years, Hungary has long

been regarded as a gateway between Eastern and Western Europe. Much more

than several of its neighbors, Hungary has had access to information about

developments in the West. Even when Western styles were condemned and when

artists who incorporated Western ideas into their work were unable to exhibit

or to publish, developments in foreign culture were part of the Hungarian

cultural dialogue. In contrast to the situation in the West, however, a

marketplace has never ex-isted for Hungarian art.

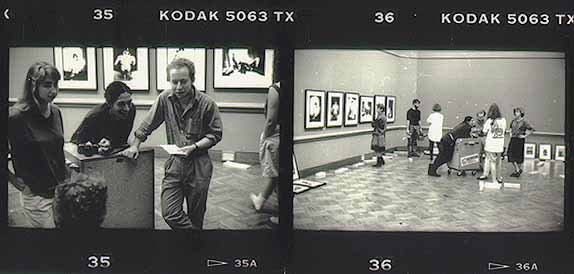

Only one “independent” gallery exists for exhibitions

of Hungary's young experimental artists. The Liget Galéria in Budapest

has been open for six years under the directorship of Tibor Várnagy. Funding

for the Liget comes from the leaders of the district of Budapest in which

it is located. They receive funds directly from the State to use as they

deem appropriate. The situation is somewhat unusual in that funding for

culture is usually provided by the Hungarian Ministry of Culture. As the

economic situation in Hungary has decayed, however, funding has disappeared

for all but Hungary's largest cultural institutions, with the result that

independent galleries have been forced to close their doors. Only the Liget,

its source of revenue undiminished, has survived.

Under Várnagy's leadership, the agenda of the Liget

has proven somewhat enigmatic. Together with Marek

Grygiel, director of Warsaw's Mala Galeria, and Dr.

Gerlinde Schrammel, director of the Fotogalerie Wien, Várnagy has arranged

for exchanges of exhibitions between Hungary, Poland, and Austria. Since

1986 the Liget has hosted exhibitions by such diverse international artists

as Milan Knízák (Czechoslovakia), Kirsten Thomas Delholm (Denmark), and

Hermann Nitsch (Austria). Programs have ranged from exhibitions to performance

art and video, to poetry readings and concerts. Within the confines of

the Liget, Várnagy has constructed an astonishing dialogue between artists

of many cultures; each exhibition appears to build upon the one that preceded

it.

Without the demand for novelty that a marketplace tends to create,

Hungarian artists have been more or less free to develop their ideas privately,

incorporating elements from their own culture as well as from others. The

enforced privacy of their production grants them the freedom to work and

re-work an idea over prolonged periods, which is quite unusual to those

familiar with the relentless trendsetting of Western, particularly American,

art. Increasing opportunities for Hungarians to participate in an international

artworld is simultaneously a welcome and intimidating new element in the

lives of many artists. It is a situation that the Liget Galéria has helped

artists to cope with, encouraging them to main-tain the Hungarianness of

their work by providing them with an athome space in which to develop,

and by offering examples of related experiments from beyond the Hungarian

borders.

The artists in the present exhibition are related

far more by the Hungarianness of their works than by their relationship

to the Liget. As a whole, their work is indicative of a Hungarian photographic

tradition largely unknown in Hungary before the 1960s, informed by the

images and ideas of Hungarian émigrés, such as André Kertész and László

Moholy-Nagy. From Kertész these artists have learned the tradition of the

Subjective photograph, which developed extensively in the post-World-War-II

photography of Western Europe and the United States, but was forbidden

in the East. From Moholy-Nagy, they have learned how to transcend the simple

making of pictures in order to develop suggestive visual forms, and how

to explore the potential of their materials, a significant skill in times

when equipment and/or materials are scarce. From both Kertész and Moholy-Nagy,

as well as from the likes of Brassai, Kepes, and Munkácsy, Hungarian artists

have gained the pride of knowing that many signifi-cant developments of

twentieth-century photography have been determined by Hungarian artists.

As deeply rooted in a buried Hungarian culture as

these works are, they are simultaneously informed by Socialist Realism,

both in their use and rejection of its restrictions. The photographers

in this exhibition do not accept the value of the photograph as evidence.

In their images reality is either absent or is presented as absurd. The

truth that they offer is unyielding. Deeply personal to the point of obscurity,

these images refuse to be defined by the terms of an officially sanctioned

reality.

The relationship of these photographs to Western Conceptualism is also

abstruse. In 1976 László Beke charted this rela-tionship, listing “radically

new principles” in photographic production as having been anticipated by

Hungarian artists of the 1960s:

What have these new principles been? The following

issues came in-to the light: The relationship of reality and artistic reality,

the setting and expanding of the borders of art, the nature of the epistemological

and social function of art. To what degree can the “picture” of reality

be identified with reality... Is art entitled to deal with subjects “strange

to its genre” like e.g. time? (The representation of processes, the depiction

of momentary events.) Can a “picture” intervene in reali-ty itself?...

Starting from the undoubtable social role of mass com-munication media:

can art make use of these media? If so, what are these media in fact? How

does art itself behave as a medium? (12)

Conceptualism offered Hungarian artists the development of highly private

forms of visual language, obscure to the cen-sors yet highly readable to

their intended audience. Thus a form of Conceptualism dealing explicitly

with the relationship of the artist to institutions of power, a distinct

precursor to American post-modern photography, has flourished in the work

of Eastern European photographers. Similar in appearance to much Western

photographic Conceptualism,

this work often incorporates elements from performance art. However

it possesses little of the humor of American artists such as Hollis Frampton,

whose photographic works poked fun at the assumed veracity of scientific

uses of the medium. Rather, Hungarian Conceptualism' is more closely related

to European Action art, such as the work of Hermann Nitsch, Joseph Beuys,

and Milan Knízák.

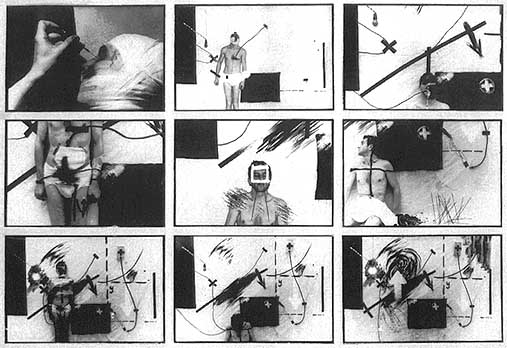

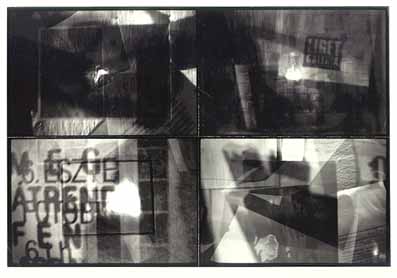

Tibor Hajas: Tumo I, 1979

Action art has continued as a viable form of expression in Eastern Europe.

The collaborative photographs of Tibor Hajas

and János Vetö made during the 1970s, for example, offer a profoundly disturbing

response to the restrictions of official culture. The first of nine photographs

in the series “Tumo I” presents a close-up of Hajas, his face burned

and wrapped in gauze, inserting a syringe into his eye. In other images

his wrists and genitals appear to be electrically wired, and long needles

are inserted into his nose. The backdrop of the photograph, from which

Hajas has disappeared in the final frame, presents a mass of Constructivist-like

forms, abstracted from their historical context. The corrupted forms, like

the mutilated body, have become useless signifiers. In similar works Hajas

is shown tied and suspended, standing with his genitals exposed over flames,

and masturbating while explosives ignite nearby.

Language has historically formed the foundation

of Hungarian selfdefinition, and until the nineteenth century Hungarian

culture was largely language-based. Unique to the artists in this exhibition,

however, is their use of the photographic medium to reveal the failure

of language. If reality is constructed through ordering (visual or verbal)

language, and if, through language, reality (history, cultural order) has

been conscripted into foreign service and falsified, then language must

be understood as having failed its people.

As much as the works in this exhibition are indicative

of a dissatisfaction with the situation in Hungary in general, and with

the role of culture in specific, they expose a distinctly optimistic element

combined with melancholy. In revealing the failure of language, the last

vestige of traditional culture, this Hungarian photography has abjured

its long relationship with the social representations of Socialist Realism

in order to address deeply felt spiritual needs. A new kind of order, the

private order of a spirituality that predates cultural history, has emerged.

The photographs of Lenke Szilágyi emerge

from the profound rupture in contemporary Hungarian photographic discourse

between social reportage, much of which descends directly from the aesthetic

of Socialist Realism, and Subjective photography. In contrast to the social

orientation of reportage, the Subjective photograph focuses upon the individual

and the search for an inner truth. The development of a subjective style

of photography in Western Europe and the United States after the Second

World War was not followed in Eastern Europe. Socialist Realism imposed

the truth of Socialist society over the truth of the individual in the

Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Individualism, regarded as an implicitly

corrupt remnant of Western influence, was prohibited. During the thaw of

the 1960s the Subjective photograph appeared among other oppositional forms

in Hungarian photography.

Szilágyi's photographs are reminiscent of the earliest

photographs of Kertész, made in Hungary shortly before he emigrated to

Paris. Her images descend directly from the tradition of the “decisive

moment,” established by Kertész and Cartier-Bresson after him. What characterizes

Szilágyi's photographs, and differentiates her work from the work of her

predecessors, is the artist's refusal to provide a single, distinct subject

within the photographic frame. Immediately appealing in their realism,

Szilágyi's photographs are also ex-traordinarily disorienting.

In each of the photographs of the series “Sunday's

Photo-graphs” the landscape, more than the figures within it, dominates

the image. The figure of the artist appears in several photographs, in

which she seems to wish to merge with the vegetation. In one the silhouetted

figure's head has become a leafy branch. In another the figure lies in

a foetal crouch in dense vegetation. In the last, the figure rests on the

broken branch of a tree, looking out at the smoke-covered city below. Photographs

in which the artist is not present show figures framed by their natural

environment, yet always distinct or isolated from it. It is their clothing

or their games, or the photograph itself, to which these figures belong.

There is a potent melancholy to Szilágyi's photographs.

They speak clearly of the artist's isolation from nature and of her alienation

from culture. Perhaps the most telling image in the series is a selfportrait

of the artist sitting alone on a plain bench in a stark room. The artist

looks at a chicken that is eating from the floor. A window at the side

of the room is sealed. Where other photographs in the series suggest the

dislocation of the figure within his or her natural surroundings, this

image depicts the absolute containment of nature by culture, and of the

artist as central to it.

Minor White, an early proponent of Subjective photography in the United

States, defined the inner search characteristic of the style by declaring

that “ever since the beginning, the camera points to myself.” In Szilágyi's

photographs this inner search is undermined by the trappings of culture,

which has come to use and define nature for its own purposes. Szilágyi's

camera points to the absence of self, the impossibility of inner truth

in a world where natural order has been subsumed by cultural order.

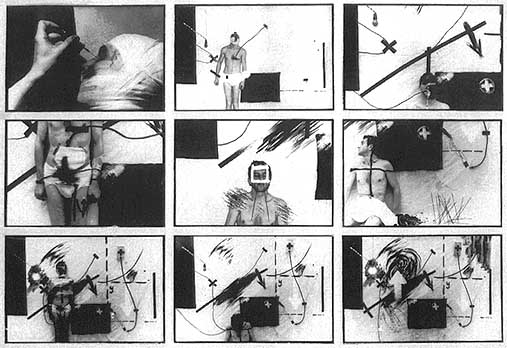

“The Great Fehérvár Flood” is the collaborative

project of László 2. Hegedüs and László Lugosi-Lugó. Hegedüs is a graphic

artist who has worked ex-tensively with film and photography. Lugosi-Lugó

is a documentary photographer. With his wife, Aljona Frankl, he

has worked for years documenting various elements of con-temporary

Hungarian culture. In the “Shops Series” Frankl and Lugosi-Lugó

recorded the growth and decay of the “Hungarian economic miracle,”

the privatization of small shops to stimulate the economy. Simultaneously,

Lugosi-Lugó has documented the gradual disappearance of elaborate neon

signs, constructed in the 1950s, from the streets of Budapest as the face

of the city changes.

László 2 Hegedüs: Untitled from the series

"The Great Fehérvár Flood" (1989)

Fehérvár is a small city south of Budapest. Its distinctive

old town center has been beautifully reconstructed, whereas countless nondescript

concrete high-rise buildings line its outskirts. The city is at once the

site of tourism and the home base of the Soviet occupational forces in

Hungary; it is, in other words, a site of conflict. There is no river or

sea near by that could possibly cause flooding. “The Great Fehérvár

Flood” is an elaborate fantasy. It presents the dual possibilities

of an indiscriminate washing away of post-war culture and a much needed

cleansing of the debilitated Hungarian soul.

“The Great Fehérvár Flood” is a powerful

incrimination of the imposition of Socialist Realism on all aspects of

Hungarian culture, and of that culture's disappearance behind the facade

of reconstruction. Beautiful as it may be, the reconstructed city center

is no different from the highrise workers' housing in these photographs.

It is less a tribute to Hungarian architectural tradition (most of which,

after all, reflects the cultures that have dominated Hungary) than to the

wisdom of the Central Committee who recognized in the city a stopover for

tourists on their way to Lake Balaton. The flood washes away the history

of Hungary's domination, the ideological landscape, from official buildings

and workers' housing to private shops and monuments to the Liberation.

Its rising waters hint at the possibility of a rebirth of Hungarian culture.

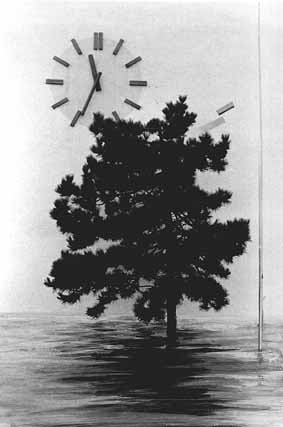

Zsigmond Károlyi's untitled series offers his audience

quite a different view of Hungarian reconstruction. As in so many Eastern

European cities, post-war reconstruction has been slow to occur in Hungary,

and hous-ing is poorly maintained. Many of Budapest's old buildings are

suspended in scaffolding, much of it quite old. In Károlyí s photographs

these wooden structures offer dual significance. Hand painted onto the

photographic paper using old or poor photo-chemicals, the images appear

to be physically disappearing from the edges of the print as much as they

are, in fact, chemically decaying on its surface. Károlyí s scaffolding

is a none-too-subtle indictment of the Socialist regimé s failure to live

up to its promises.

Zsigmond Károlyi: From Scaffold Series # 14, 8

On a very different level, Károlyi's photographs

indicate the frailty of the remnants of Hungarian culture. In speaking

about the geometric “X” motif in his photographs, the artist gestured

at the scaffolding that holds up the inside walls of his studio. These

structures, hidden from the view of the public, support the room in which

the artist has lived and worked; without them the walls would quickly weaken

and fall. Like “The Great Fehérvár Flood” Károlyi's photographs

speak of the disappearance of Hungarian culture behind the facade of reconstruction.

Further, Károlyi questions what would remain following the dissolution

of imposed culture. Frail as they may be, these structures support the

artist's work. Prophetically Károlyi poses the question now plaguing Hungarian

political reformists: With what shall we replace that which is all we know?

Károlyi's photographs speak of the interior definition

of the artist by exterior forces, of the struggle to find a voice of one's

own in circumstances where the only known language supports a decaying

structure. The photographs of István Halas reveal a similar struggle. Using

only photographs made inside his small studio, Halas combines fourteen

negatives in each of the four photographs that make up the individual “Sonnets”

in the series “Sonnets I-V.” In this series, Halas speaks eloquently

of the artist's difficulty in finding a place within the structures of

Hungarian culture without perpetuating its terminology.

Like Károlyi, Halas was trained as a painter.

His work with photography has fluctuated from portraiture to landscape

to “interior landscape,” using both color and black and white. His

earlier work with portraiture and land-scape was distinctly influenced

by Western photographic trends. In his minimalistic landscapes, Halas attempted

to bridge cultures using unifying elements from the architecture of different

European and American cities. Halas' work with photographic tableaux, of

which “Sonnets I-V” is the most recent series, represents a retreat

from his earlier efforts.

Sonnet 1 depicts a photocopy of a portrait of Robert Frank by

Richard Avedon, one of many images hanging in Halas' studio. The photograph

is significant in its representation of two artists whose radically different

approaches to photography have greatly influenced Halas' earlier work.

Here it signals a departure both from the influence of these artists and,

by extension, from the dicta of Western photographic trends.

In Sonnet II crumpled paper and cigarettes

lie on the studio floor. The graphic image of an umbrella, used in a collaborative

film of Halas and László 2. Hegedüs, and a pin commemorating the Polish

Trade Union Solidarity appear, as does a wall label used in an earlier

exhibition of Halas' work. In Sonnet III, the black frame of a single

photographic image is obscured by the text of a poster from the Esztergom

Foto Biennial. Sonnet III also contains an earlier work, a simpler

tableau of four photographs of the stairwell to Halas' studio. In the fourth

and final image, a glowing lightbulb is montaged with the insignia of the

Liget Galéria taken from a poster designed by the artist. Behind the bulb

and the insignia looms the first of Halas' complex tableaux, made in 1986.

This early work encapsulates the history of Halas' development as a photographic

artist, beginning with his first and ending with his most recent image.

Sonnet IV and Sonnet V return the

viewer to the objects of the artist's studio. A copy of the catalogue Bilder

recalls the exhibition of Hungarian photographers at the Photogalerie Wien

in which Halas' tableaux made their first public appearance. The outline

of a hand obscures the image of a single--frame photograph and the form

of a long strip of film overshadows a pile of prints. Finally, the word

“zenit” (zenith) emerges, suggesting that the artist has found, within

the confines of his studio, his own voice.

In “Sonnets I-V,” Halas presents a series

of juxtaposing signs that show the crosscurrents of his life as an artist.

His photographs are distinctly selfreferrential; the artist speaks only

for himself. He confines himself to his studio, but that small space is

filled with signs from the outside. “Sonnets I-V” is a dialogue

of signs, many of which are but notes by the artist to himself; they are

the origins of a private language and, as such, offer little information

to the viewer. It is in the juxtaposition of these private signs with others

from the outside that the viewer is encouraged not so much to understand

the artist, to seek reassurance in his images, as to engage in the dense

visual process that he has begun. The photocopied Avedon portrait represents

a removal from the sleek, formal surfaces and highly public life of one

artist (Avedon) to the obscure meaning, damaged surfaces, and highly reclusive

life of the other (Frank). At least a fourth-generation copy of the original

and rephotographed by Halas only in pieces, the photocopied portrait depicts

a physical tearing away of the image from its context in reality, from

cultural order. The glossy poster from the Esztergom Foto Biennial, a place

where conformity to genre and institutionalized practice are encouraged

and rewarded, is juxtaposed to the insignia of the Liget Galéria, where

the development of the private language of the artist, as free from influence

as it is free to appropriate the terms of influence, is encouraged.

Halas' photographs speak of the search for self

through the subversion of meaning in visual forms. Like Zsigmond Károlyi,

he presents a response to official culture while recognizing that the work

of the artist, particularly if it is to achieve public response and support,

must always be deeply rooted in its terminology. The terminology by which

the ar-tist is defined in the photographs of Zsuzsanna Ujj are, by contrast,

archaic. They are the signs of an imposed cultural order that far predates

the Hungarian Liberation.

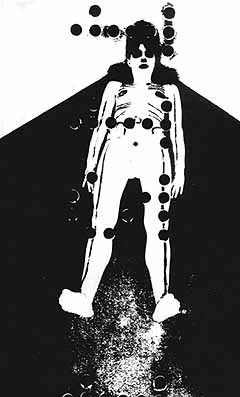

Ujj is a poet, performer, musician, and visual artist

who works exclusively outside the Hungarian system of directed culture.

She is one of the few Hungarian artists who continues to link performance,

Action art, and photography. Exhibitions of her photographs have often

been accompanied by performances and documentation.

Ujj’s work deals powerfully with the cultural representation of gender,

the power of sexuality, and, ultimately, with the dual relationship of

sex to death and of representation to violence. In one photograph, the

artist sits upon a fabricdraped chair that rests on a platform. Her body

is painted to emphasize her eyes, mouth, breasts, and vagina. Her position,

looking down at the camera, is one of power. A second image shows the painted

body swooping down upon the viewer. Her arms and legs disappear into the

black background. Her mouth is open as if in a scream, her look menacing,

devouring. In the third image of the series, the artist stands with the

figure of Death. Death is a man in a dark suit; the artist’s hand rests

provocatively on his leg.

Ujj’s work deals powerfully with the cultural representation of gender,

the power of sexuality, and, ultimately, with the dual relationship of

sex to death and of representation to violence. In one photograph, the

artist sits upon a fabricdraped chair that rests on a platform. Her body

is painted to emphasize her eyes, mouth, breasts, and vagina. Her position,

looking down at the camera, is one of power. A second image shows the painted

body swooping down upon the viewer. Her arms and legs disappear into the

black background. Her mouth is open as if in a scream, her look menacing,

devouring. In the third image of the series, the artist stands with the

figure of Death. Death is a man in a dark suit; the artist’s hand rests

provocatively on his leg.

Ujj’s poses in her photographs are often reminiscent

of prehistoric figurines of the Goddesses of Fertility. Such figurines

are thought to have commemorated the relation of the fertility of women

to nature, and to “give magical aid in childbirth and conception.” (13)

In her earliest representations, the Goddess was depicted as the source

of life, and intercourse with her the source of knowledge; like nature

itself, she was untamed. In the course of history, however, nature came

in-creasingly to serve the needs of man and reproduction became an integral

part of his economic development. (14) The role of women, and with it the

perception of the Goddess, changed.

Artemis-Diana, once the wild mother of vegetation...was

rendered chaste and frigid, she was made into a virgin. She no longer fetched

men into her womb, but rather struggled against those who pursued her in

order to watch her bathe in the nude. Later on this Diana was compared

with the Virgin Mary...Intercourse was less and less knowledge, it developed

into a menace. The vagina acquired teeth. It ate and devoured. (15)

Like Halas, Ujj makes photographs that are selfreferential.

The setting of her photographs is always an anonymous space within which

darkness encroaches from all sides, reminiscent of the caves in which Goddess

rituals were performed. In one photograph, a bright light illuminates and

beckons the viewer to her womb. In the next, her blurred and bleeding figure

appears in pain (fig.10). In the final image, a horrible, bloody mass emerges

from her. In these images, Ujj represents a powerful Goddess whose sexuality

must be feared. The Goddess is no longer connected with nature, nor does

she bear any relationship to the Virgin.

Ujj's photographs struggle against the historical

violence of the representation of women by focusing on sexuality as an

imposed cultural construction. Through a series of con-frontational poses

directed at the viewer, recognizable through their appropriation of sexual

symbols, Ujj undermines her audience's “innocent gaze.” To strike a pose,

as Dick Heb-dige has written, is to pose a threat. The anonymous space

of the Ujj's photographs extends to the space of the gallery or museum;

the threat of her pose extends to the viewer within it. Returning the gaze

of the viewer Ujj defies the borders of the print. Her photographs transform

the gallery, and with it the tradition of the passive female nude that

it represents, into a site of confrontation.

János Vető's photographic constructions,

like those of István Halas, are unyielding and enigmatic; they are composed

of many layers. In subject and construction they are both striking and

defiant. Well known in Hungary for his work as a musician, especially as

a member of the legendary“cassette band” Trabant, Vető is also recognized

for his profoundly influential work with the late Tibor Hajas. His photographic

work, made under the pseudonym “Kina,” is inconsistent, ranging from the

hand-painted series “Poisoned Candies” to documentation of his visit

to the United States made with a low-grade Soviet camera, the “Lomo.” His

works are often presented in unusual installations.

The present series of Vető's photographs was first

exhibited in Budapest in 1989 at the Contemporary Art Forum of Almássy

Square. For the installation, the series was attached to hinged, book-like

binders that were attached to a random pile of hard wooden chairs. The

chairs were stacked on top of a similar pile of tables and desks. The tables

and chairs are the same as those in which students sit to study in Hungarian

schools and cultural houses. Vető's photographs are intended to turn the

academy upside down.

Vető's subjects are the things with which he surrounds

himself: pencils, cigarettes, a jar full of paint brushes. In his photographs,

however, familiar things are removed from their usual context. Their cultural

use, and thus their function as objects within culture, is robbed from

them. In photographs such as Gitárlecke Földönkivülieknek (Guitar Lesson

for Ex-tra Terrestrials) and Black Could Flag, his materials

seem to have been elaborately arranged in abstract patterns for the artist's

own amusement. Considerably more enigmatic are the photographs Cave

and Realiti. In the densely layered Cave, documents, a palm leaf, and fabric

encircle halfnaked women wearing pig masks. In Realiti, a plastic female

doll, whose physical features have been scratched by the artist into the

negative, is attacked by a rubber bat and dinosaur; all other details of

the image have been obliterated by the ar-tist's scratching away the emulsion

from the film.

Vető's photographs defy classification. His Still

Life is not still, but is constantly disappearing and re-emerging as the

eye focuses upon the different elements that it contains; its brushes fade

from view as the eye discovers the outlines of palm leaves. Realiti is

not reality; rather, it is a haphazardly constructed joke. Perhaps an oblique

reference to Plato's cave, the figures that emerge from the shadows of

Cave mock the viewer's search for meaning and reassurance in the photograph,

just as Black Could Flag, apparently a stain on film, transforms

the symbol of patriotic fervor to an abstract and useless form. By emphasizing

inchoate form, Vető's photographs seem to represent the dissolution of

reality and the laughable condition of those who continue to hold to it.

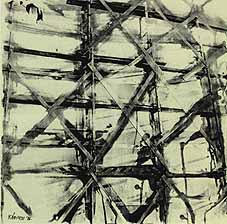

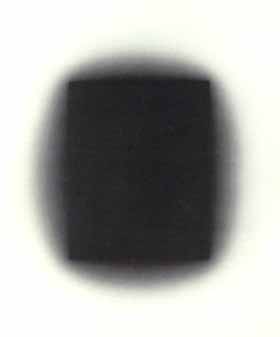

The photographs of Tibor Várnagy recall the experiments

of Russian Suprematist Kazimir Malevich at the turn of the century, and

the cameraless photographs of Moholy-Nagy. The Suprematist vision of Malevich

existed as a spiritual counterpoint to the revolutionary social vision

of the Russian Constructivists. (16) In con-trast to the Constructivists,

Malevich sought pure form in art, form as it emerges from raw material.

He believed that the depiction of things, the reproduction of nature, was

indicative of “cowardly consciousness and insolvency of creative power

in an artist.” “The square is a living, regal infant,” Malevich declared

in 1916. “The first step of pure creation in art.” (17)

The path charted by Malevich toward the purity of

form, toward the artist as a “null” freed from slavery to the obligations

of art, was profoundly influential to the young László Moholy-Nagy. Whereas

the pursuit of pure form was for Malevich an inquiry into human spirituality,

for Moholy-Nagy “religion simply did not exist.” (18) Moholy-Nagy believed

that art was “the activation of the energies of the subconscious through

the optical organ of the eye...the education of man's subconscious.” (19)

It was an educational process in which he saw photography playing a primary

role.

In the pursuit of pure form in photography, Moholy-Nagy

advocated the use of the cameraless photograph. “The photosensitive layer-plate

or paper-is a tabula rasa where we can sketch with light in the same way

that the painter works in a sovereign manner on the canvas with his own

instruments of paintbrush and pigment,” he wrote in 1928, in the publication

Bauhaus. “Whoever obtains a sense of writing with light by making photograms

without a camera, will be able to work in the most subtle way with a camera

as well.” (20) In his photograms, Moholy-Nagy demonstrated how photo-graphy

could accommodate the Suprematist experiments in pure form.

Várnagy's photographs combine Malevich's spiritual

quest with the technological consciousness of Moholy-Nagy. His Four

Black Squares and Fifth Black Square emerge from a devotion

to photographic experimentation and from his development of schnass. An

obscure word originally used by German guestworkers in Hungary to describe

the poverty of the Hungarians and their culture, schnass is the term used

by Várnagy to describe his practice of working exclusively with Hungarian

photographic materials, and eliciting from them their inherent qualities.

Underlying Várnagy's photographic experimentation

is a dialogue with Hungarian culture. In the series “Strabizmus”

(1986), for example, Várnagy used many small sheets of paper to create

a large image. The manufactured sheets were poorly cut, and when placed

together in a large rectangle gaps showed between them. The gaps became

an integral element in the overall work. In his Four Black Squares

and Fifth Black Square, Várnagy found his materials incapable of

yielding a perfect edge; light consistently permeated whatever borders

he constructed to inhibit it. This work acts at once as a return to the

spiritual quest of Malevich's Black Square, and as a poignant indicator

of the social and material poverty that necessitates such a quest.

Tibor Várnagy: Black Square, 1988

In common with many other artists, Várnagy's photographs

are indicative of a departure from realism, the desire to divest objects

of meaning by denying the validity of their cultural functions. In his

work with cameraless photographs, Várnagy has been particularly successful.

His series of “TV Contacts,” made by holding pieces of photographic

paper against the television screen, transformed the everpresent features

of newscasters to pure form. Removing them from their context, from the

distrusted, Statecontrolled media, Várnagy effectively robbed the newscasters

of their role as the determiners of Hungarian reality and culture. His

work with a camera, distinguished by a marked decay of the image created

by reproducing the negative numerous times before printing, has accomplished

similar results by underscoring the role of the artist within Hungarian

cultural production.

“The group of suprematists. . . has waged the struggle

f or the liberation of objects from the obligations of art,” Malevich wrote

in 1916.(21) That struggle continues in the work of Várnagy, who recognizes

the only real liberation as spiritual. Only through such liberation will

the artist rediscover his relationship to the world of natural forms, from

which a new language can be constructed. Only through the emergence of

such a new language will the imposition of ideological values upon pure

form disappear from art, and a new Hungarian culture appear.

Today Hungary, with Poland, is charting the future

of Eastern European political and social life. The singleparty system is

opening up to embrace the plurality of voices that has always existed there.

The disappearance of borders, however, does not necessarily imply the arrival

of independence. More than most, Hungary's artists are aware of the encroaching

influence of the West. What they seek, as domination from the East fades

and the influence of the West beckons, is the rediscovery of their own

traditions and histories. In Hungary, language has always served as a uni-fying

factor, as that which distinguished Hungarian tradition and history from

the histories and traditions imposed upon the Hungarian people by the Turkish,

the Austrians, the Germans, and the Russians. To explore visual language,

to remove from it the remnants of dishonor and servitude and to uphold

in it that which has, somehow, retained its purity, is the goal of these

artists. By looking into themselves, by liberating form from ideological

domination, they are rewriting their own histories. In the work and spirit

of these artists, the language of independence is being born.

I have released all the birds from the eternal cage

and flung open the gates to the animals in the zoological gardens. May

they tear to bits and devour the leftovers of your art. (22)

NOTES

1. Zoltan Halász, ed., Hungary: Geography, History, Political and

Social System, Economy, Living Standard, Sports, Budapest, 1963, p.

343.

2. Alexandr Rodchenko in Thinking Photography, ed. Victor Burgin,

London, 1982, p. 178.

3. Daniela Mrázková and Vladimir Remes, Early Soviet Photography,

Oxford, 1982, p. 9.

4. Ibid., p. 10.

5. John E. Bowlt, “Alexandr Rodchenko as Photographer,” in The

Avant-Garde in Russia, 1910-1930. New Perspectives, eds. Stephanie

Barron and Maurice Tuchman, Cambridge, Mass., 1980, p. 58.

6. John E. Bowlt, ed., Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and

Criticism, 1902-1934, New York, 1988, p. 291.

7. Peter A. Toma, Socialist Authority. The Hungarian Experience,

New York, 1988, p. 76.

8. Miklós Haraszti, The Velvet Prison. Artists under State Socialism,

New York, 1987, p. 100.

9. Ibid., p. 37. 10. Ibid.

11. Vaclaw Havel, A Besieged Culture. Czechoslovakia Ten Years after

Helsinki, Stockholm, 1985, p. 133.

12. László Beke, Expozició, Hatvan, Hungary, 1977, n.p.

13. Joseph Campbell, The Masks of God. Primitive Mythology,

New York, 1959, p. 139.

14. Gayle Rubin, “The Traffic in Women,” in Toward an Anthropology

of Women, ed. Rayna R. Reiter, New York, 1975, pp. 1S7-210.

15. Hans Peter Duerr, Dreamtime. Concerning the Boundary between

Wilderness and Civilization, New York, 1985, p. 43.

16. Michail Grosman, “About Malevich,” in The Avant-Garde

in Russia, 1910-1930, p. 25.

17. Kazimir Malevich, “From Cubism to Futurism to Suprematism: the

New Painterly Realism,” in Russian Art of the Avant Garde. Theory

and Criticism, p. 133.

18. Krisztina Passuth, Moholy-Nagy, New York, 1985, p. 25. 19.

Ibid., p. 319.

20. Ibid., p. 303.

21. Kazimir Malevich, “From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism:

The New Painterly Realism” in Russian Art of the Avant-Garde:

Theory and Criticism, p. 135.

22. Ibid.